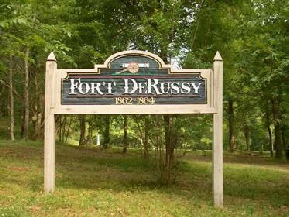

Friends of Fort DeRussy, Inc.

The Official Site of Fort DeRussy, Louisiana

THE ORIGIN AND INITIAL HISTORY OF

FORT HUMBUG

AVOYELLES PARISH, LOUISIANA

The "Humbug"

The name Fort Humbug would appear to have been unofficial, and probably stemmed from

the average soldier's belief that the fort was, in fact, totally useless. In a letter

to his wife dated December 20, writing from "Camp on Bayou Des Glaise," six miles

from Simmesport, Dr. Edward Cade of Walker's Division stated "Our command is engaged

in throwing up quite an extensive line of earth works, though I think it labor thrown

away as they are perfectly useless."[12] Captain Elijah Petty, of Company F, 17th

Texas Volunteer Infantry, Scurry's Brigade, explained the situation in a letter home

to his wife in mid-

"This is one of the routes by which Ft. DeRussy can be flanked. But there are 3 other routes by which it can be flanked either of which isas good or better than this and why this alone is defended is more than I can tell. The other routes that I refer to are 1st By the way of Berwicks Bay, New Iberia etc the way that Genl Banks approached Alexandra last spring, 2nd By the way of Morgan's ferry[13] up Bayou Rouge by Cheneyville etc, and 3rd and best route is up Red River, up Black river, up Little River through Catahoula lake and by water to within 18 miles of Alexandra. If we had a force and works to guard all these routes I could see some practicability in the work that we are doing here. Otherwise it appears nonsensical."[14]

Another problem that existed with the defense of Fort Humbug was the fact that its southern flank was defended solely by a usually impassable swamp, which would be dry and quite passable in March of 1864, leaving the fort completely susceptible to encirclement.[15]

Not everyone felt that Fort Humbug was a fraud, however. One Confederate staff officer, Felix Pierre Poche, castigated General Scurry for abandoning the fort, feeling that the Texans should have been able to hold the position in spite of being outnumbered twelve to one![16] In a March 13, 1864, diary entry, Poche stated "I learned that Genl Scurry in needless fright had foolishly retreated before the enemy, abandoning his well constructed and formidable camp on Yellow Bayou in the night on Saturday."[17]

Union Knowledge of Fort Humbug

Union forces had been made aware of the construction of Fort Humbug by early January 1864. On January 7, Charles C. Dwight, Commanding Officer of the 160th New York Volunteers, reported receiving word from Lt. Commander Frank M. Ramsay, commander of the gunboat squadron at the mouth of Red River, that "the enemy is fortifying at the junction of Bayou Yellow and Bayou DeGlaize, about 1 mile west of the Atchafalaya."[18] In a report dated January 8, Lt. Commander Ramsay officially reported learning from a refugee that "A small fortification has been built back of Simmesport at the junction of Yellow Bayou with Bayou des Glaises, and there is a breastwork, with a couple of fieldpieces, about half a mile below Simmesport, on the Atchafalaya."[19]

By January 12, Ramsay had picked up "several deserters and refugees" and noted that "They also confirm the report about the fortification at the junction of Yellow Bayou and Bayou des Glaises. Scurry's brigade is stationed there. He has only field guns."[20] More confirmations followed. On January 23, Brigadier General George L. Andrews (Commanding, Port Hudson), reported "Two negroes just in from Grosstete report 600 of Walker's command were at that place on Wednesday last conscripting colored men, mules, and oxen, to be used on fortifications at Simsport, which place the rebels are reported to be fortifying."[21] On January 28, Brigadier General Daniel Ullman, also at Port Hudson, reported that four deserters, one refugee, and one prisoner had been brought in, and had provided information "that General Walker has erected a large and strong work at the junction of Yellow Bayou and Bayou De Glaize."[22]

The "Grand Skedaddle"

General A. J. Smith of the United States Army arrived at Simmesport on Saturday,

March 12, 1864, with approximately 18,000 men (21 regiments of infantry, 3 batteries

of light artillery, and elements of the Mississippi Marine Brigade).[23] First indications

were that the landing would be made with about 2,000 men, and Scurry's Brigade made

preparations to defend against this attack. When the true scope of the invasion

was discovered, Fort Humbug was abandoned, and the "Grand Skedaddle" was on, not

to end until April 8, near Mansfield where the "skedaddle" would reverse, and turn

into one of the last great Confederate victories of the War. Meanwhile, Scurry's

Brigade moved to near Moreauville, where it linked up with the rest of Walker's Division.[24] Wagons

were sent back to the old camp site for tents and other baggage, but this resulted

in the capture of several wagons and drivers, and the tents were lost anyway.[25] As

the Union column moved past Fort Humbug on the morning of March 13, they found "the

camp broken up and the enemy gone; the bridge leading across the stream burning,

and evidence of a fright. There were two extensive earthworks, still incomplete,

and a prodigious raft being constructed across Bayou Glaize so as to prevent the

gunboats ascending the little channel during high-

The Yankees Return

The abandonment of Fort Humbug marked the opening of the Red River Campaign. Two

months later the fort was involved in the final days of that campaign. The Union

attempt to enter Texas had been a failure, and on May 17, 1864, the lead elements

of the whipped army of some 30,000 troops were being driven past Fort Humbug by a

Confederate army about one-

Homer Sprague, of the 13th Connecticut Infantry, reported passing "some new and strong fortifications on Yellow Bayou, the principal of which was called Fort Lafayette. The rebels evacuated them at our approach."[28] The 83rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry "followed Bayou LaGlaze and crossed a small bayou at Fort Taylor, which was being leveled by pioneers."[29] About noon on the 17th, the 114th New York State Volunteers "crossed Bayou Yellow upon a pontoon bridge, passing through some rebel works which were commenced a year before, with the intention of holding the road and the crossing. They were well planned, upon an extensive scale, but the enemy being compelled to change his line of defense, they were abandoned unfinished."[30]

Destruction of Fort Humbug

Colonel George D. Robinson, Commanding Engineer Brigade, had arrived at "Yellow

Bush Bayou, 3 miles from Simsport," at 4 AM on May 17. By 6 AM he had a pontoon

bridge ready to cross troops, and encamped his Third Engineers "on the east bank

of Yellow Bush Bayou. On the west bank of the bayou the enemy had constructed two

formidable earth-

Fort Humbug in the Battle of Yellow Bayou

At the beginning of the Battle of Yellow Bayou on May 18, 1864, the 33rd Missouri

Infantry received orders to move from "the rear of the levee on Avoyelles Bayou,

and take a position in the center of the field, in front of Fort Carroll and on the

left of Battery M, First Missouri Light Artillery."[33] Arthur McCullough, of the

81st Illinois Infantry, mentions forming a line across the bayou from a fort while

"a brisk fight took place across the bayou opposite us."[34] There is also an article

from a Galveston newspaper concerning the battle, presented as a third-

Various Names

There appears to have been no official name for Fort Humbug. The soldiers who built the fort referred to it as Fort Humbug. The Union troops who observed it referred to it (or its component parts) variously as Fort Humbug, Fort Scurry, Fort Taylor, Fort Lafayette, Fort Morgan, and Fort Carroll.[37]

Notes

[1] The first recorded mention of the construction of the fort was by Captain Elijah

Petty in a letter to his wife, dated December 15, 1863: "I expect we will remain

near this place some time as we have commenced fortifying at Yellow Bayou about one

or two miles further up Bayou De Glaze than our present camp." Brown, Norman D. Journey

to Pleasant Hill: The Civil War Letters of Captain Elijah P. Petty, Walker's Texas

Division, CSA, pp. 292-

[2] Private J. P. Blessington gives this date as March 5. "On the morning of the 5th, General Scurry's Brigade quit work on the fortification known as Fort Humbug, on Yellow Bayou, which proved afterwards a very appropriate name." Blessington, J. P. The Campaigns of Walker's Texas Division, p. 166. Petty said that work had been suspended on the 3rd. Brown, p. 374.

[3] Blessington, p. 169-

[4] Brown, p. 304.

[5] Brown, pp. 293, 294, 304.

[6] Blessington, p. 158. Bearss, Edwin C. A Louisiana Confederate: Diary of Felix Pierre Poche, p. 89.

[7] Brown, p. 301.

[8] Brown, p. 305.

[9] Brown, p. 301.

[10] Jan. 4, 1864. "We have been to the fortifications to work to day and it had been raining on us nearly the whole time. It was mud and slosh all the time which made it hard & disagreeable work." Brown, p. 301

Jan. 7, 1864. "It has been quite cold and wet for over a week. Some little snow

fell the other night. It rains at least once a week and frequently two a week. It

is a miserably wet time and mud mud mud is all the go." Brown, pp. 301-

Jan. 11, 1864. "Last night it rained and we have slosh and mud to day. It is a safe rule to say that it will rain a least once a week here." Brown, p. 303.

[11] Brown, p. 302.

[12] Anderson, p. 85.

[13] On the Atchafalaya River, just north of the current-

[14] Brown, p. 304.

[15] Blessington, p. 171.

[16] 18,000 to 1,400. Blessington, p. 169-

[17] Bearss, p. 93.

[18] ORA 34/2, p. 36.

[19] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion,

Volume 25, pp. 679-

[20] ORN 25, pp. 684-

[21] ORA 34/2, p. 135.

[22] ORA 34/2, p. 172.

[23] ORA 34/1, p. 304. Crandall, Warren. History of the Ram Fleet and the Mississippi Marine Brigade in the War for the Union, p. 377.

[24] Blessington, pp. 169-

[25] Blessington, p. 169; Brown, p. 378; Bryner, p. 99; Moore, Frank. The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events. Volume 8, p. 430.

[26] Moore, p. 430.

[27] Williams, John M. "The Eagle Regiment", 8th Wis, Inf'ty Vols...

[28] Sprague, Homer. History of the 13th Infantry Regiment of Connecticut Volunteers during the Great Rebellion, p. 213

[29] Marshall, T. B. History of the eighty-

[30] Beecher, Harris H. Record of the 114th Regiment, N.Y.S.V., p. 353.

[31] ORA 34/1, p. 252.

[32] Author's personal opinion. No trace of this fort currently exists.

[33] ORA 34/1, p. 337.

[34] McCullough, Arthur. Diary. Entry for May 18, 1864

[35] "A Yankee Account of the Fight at Yellow Bayou, La.", Galveston Tri-

[36] Author's personal opinion. This article was written by a reporter based on information given him by a Confederate officer who had spoken to a Union officer captured at Yellow Bayou.

[37] Bryner, p. 99; Marshall, pp. 13, 144; Sprague, p. 213; ORA 34/1, p. 337; McCullough, May 18; Ambrose, Stephen E., ed. A Wisconsin Boy in Dixie: Selected Letters of James K. Newton, p. 109.

Fort Humbug was a complex of forts and earthworks constructed at the junction of Yellow Bayou and Bayou des Glaises, near the village of Simmesport in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana, for the purpose of preventing the movement of Union troops into central Louisiana. Its construction was begun shortly before December 15, 1863 [1], by Scurry's Brigade of Walker's Texas Division, Confederate States Army, and construction continued on the works until March 3, 1864.[2] Fort Humbug was abandoned by Confederate forces on March 12, 1864,[3] and was destroyed by Union engineers in late May of the same year. Only a small portion of the original Fort Humbug remains in existence, and can be seen on the south side of La. Highway 1, just west of Simmesport.

Construction of the Fort

The fortifications at Fort Humbug were on the west bank of Yellow Bayou and on both banks of Bayou des Glaises, and consisted of "extensive works extending for near two miles in length," and included "forts, glacis, rifle pits etc etc."[4] The four regiments of Scurry's Brigade were camped from one to three miles up Bayou des Glaises,[5] housed in abandoned slave quarters on the Norwood Plantation,[6] and worked on the fortifications on a rotating schedule, one regiment working every fourth day, seven days a week.[7] (It was noticed, however, that "the boys don't work well on Sunday. They don't have the vim that they would on another day."[8]) Working by reliefs, the individual soldiers would work for one hour and rest one hour.[9] The cold weather and frequent rains (including at least one snowfall) made for miserable working conditions,[10] but in general the soldiers working on the fort were "living tolerable well." They had plenty of corn bread and poor beef, as well as sugar and molasses, with occasional pork, potatoes, and flour.[11]